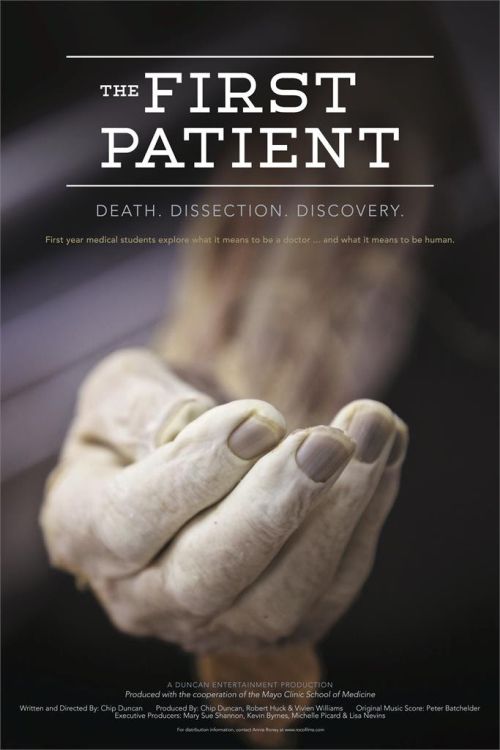

ATM: Why the title First Patient?

CD: It is on the idea that every doctor’s first patient is a cadaver. Every doctor’s first patient is dead. They meet them close up in the lab in their first year of school.

ATM: They move from death to life.

CD: They can do things with a cadaver that they are not able to do on a real patient regarding exploring the inside of a body. These are the big scientific elements. They are studying the inside of the human body. They are learning a lot about what it means to be human. This question is something that makes the film unexpected. We keep asking the questions “what are we?”

ATM: How could working on a cadaver transform a first-year patient’s view on humanity?

CD: It would not be a disservice to put the audience in the same experimental place as the student. They are learning about this in the same  sequence as the student would. The student goes into it with a lot of aphorisms. They are not a part of the business of healthcare or apart of the system regarding the controversy with pharmaceutics and drug prices. They go into it with relatively a pure vision of being a healer and trying to help. By working on these cadaver bodies, they develop a strong sense of what it means to be human. In a strong sense of approaching the frame with reverence and respect that they might not get if they walked in and worked on someone with a heart condition. There is a tenderness that comes through in this class that helps informs them.

sequence as the student would. The student goes into it with a lot of aphorisms. They are not a part of the business of healthcare or apart of the system regarding the controversy with pharmaceutics and drug prices. They go into it with relatively a pure vision of being a healer and trying to help. By working on these cadaver bodies, they develop a strong sense of what it means to be human. In a strong sense of approaching the frame with reverence and respect that they might not get if they walked in and worked on someone with a heart condition. There is a tenderness that comes through in this class that helps informs them.

For the audience, we are asking questions that we never expected to ask. I know for the other audience who have seen it so far, a lot of them are talking about donating their bodies when they never considered it before. You cannot help but ask the question of “what am I? or “where would the soul reside.” When I am dead, I am dead. We can always relive the rituals, but the rituals are for the people who are here. These are questions that come up when watching the film. They are dead.

ATM: For this reason, I am not a materialistic person. Some people idolize a lot of materials.

This film shows you cannot take it all with you. You have all these emotions. It shows the reality of death.

CD: Yes, the finality and reality of it. Even though you are gone, you still have the opportunity to be a gift to these students. It is pretty cool.

It was not something I spend a lot of time thinking about once making the film. Now I would do it.

ATM: So, you would donate your body?

CD: Yes, I would. Right now, I am a little too young to sign the donor card because my organs are still vital. This is one of the things that happens when people sign over their organs because they are brain dead. I am an organ donor right now, and soon I will become a body donor. I thought why not. It cannot hurt.

ATM: What about the families who want to keep the bodies or have a service?

CD: Overwhelming the number of people who die in the United States i cremated. In this case, the remains of the body still are cremated. There is a service at the end of the class, and the cremains of the body returned to the family so that they can organize a memorial service. They could go ahead to do the same service after the cremains are returned.

If I decide to get cremated, I still will, but I would first get dissected. It is a weird conversation to have then when you see the film; it is like why not?

ATM: The scene where one of the students holds the old guy’s brain, and they could see the modifications of age through time.

Do you think this shows neutral plasticity at its finest?

CD: Because I was photographing it, I am not sure I have the same point of view or experience that the students would have had. The one thing I would say is that there were 13 cadavers. In the film, we filmed seven cadavers. We had six students at a table. In each case, you could see an unique sex of aging on a body. One body, it would be the effects of obesity. Another might be heart disease, or another could be early signs of dementia within the brain. The students gained a lot of this because they would visit different tables. They see this is a clear indication of Alzheimer’s disease or extraordinary layers of fat. In one body we thought bodies were the heart in one body but was the difference in the heart of another body simply because of fat tissue. These are the value the student has when going to another table. We have one patient that had a pacemaker, and another that had a knee replacement. It was fascinating to see this on the inside.

ATM: Do you believe there is a need to be different human nature because of how similar our skeletons are?

When I look at skeletons, they honestly look the same.

CD: I think so too. The anatomy professors would tell you as soon as the skin get removed that everyone looks the same underneath. One person might be bigger or smaller but for the most part, the way nerves and veins become wired, we are all the same when the skin gets removed. These are interesting points to make the audience think.

Even when females and males are on the table other than the genitals, we are the same. Whatever created us is pretty fascinating. Whenever we enter the planet, we are all the same underneath.

ATM: So, is there a sense of trying to be different?

CD: Yes, our personalities are unique, our soul, and intelligence. Also, also how we decide to navigate on this planet is unique. One person is a musician, artist, mother, or father. Our difference comes from our consciousness and not from our body.

You and I could have a great conversation and get some coffee. We could find out we both like heavy metal or romantic comedies. We could come together in the same way, but the same ideas are what drives us. This really has very little do with our bodies.

ATM: A person that comes from their mother’s womb or embryo, they are put on this earth for “x” amount of years, and possibly can become a cadaver.

What does this entail about the purpose of life?

CD: Wow, this is a great question. I can tell you from my perspective. It is all about being a service and giving back. Especially once you realize the meaning of “dead.” When I look at it, I just take a more humanistic approach to it and ask, “Who did I help? Where did my generosity lead? Was I able to make the world a better place?” This is me. Someone else might see it differently. This is some of what I found in the donors we talked to and they were so altruistic.

ATM: Metaphorically, what does “dead” really mean? I know it is when your heart takes its last pump.

What about for the people who have died in our society and how their names and what they do still lives on in this world?

Some people in this society cannot let them go. Are they metaphorically still alive?

CD: They would be to you and me. We are talking about an actor, musician, and politician. Does Charles Dickens soul live on? A lot of us place value on celebrities for this reason. We want to believe something we did matter or last. Something we did in a scheme of things might last 100 years or 500 years. It does not go on beyond this. We remember Julius Caesar or Shakespeare.

What did you like about the film?

ATM: The scientific part was interesting. The caption was great. I have dissected things before, so I was not creeped out.

The finger scene was interesting to see how all the things they dissect are not in the same use once a part.

The human body took the form of a puzzle to me. It showed me that the little things on our body matter. As you said, it makes you think what humans are?

If there was another species living on another planet, what might they classify us? We view possible evidence of aliens as aliens, but in their imaginative society, they would view us as the same.

The fact that we can walk and get hit by a car in a matter of seconds. Your soul, your existence on this earth b in a split second. It’s gone. Everyone that is not lucky to should make their mark on the world.

CD: It is a good question. You would recommend the film to people?

ATM: Yes, I would only recommend the film the people are who extremely open-minded, deep, and philosophical.

CD: I see it too. I know it is not a film for everybody. There are plenty of people who would approach that are deep and philosophical.

ATM: You have to go under the surface. Over the surface, you see the pealing of human bodies. Thi =might be a huge turnoff for people.

CD: In the start of the conversation when you asked how my day was, it is definitely better when talking to you about this. You are asking more interesting questions than I have gotten from a lot of people. I am glad for this.

ATM: What did a soul mean to you before shooting this film and now what does it mean?

CD: Before making “The First Patient,” I had spent very little time thinking about the nature of the soul. As a non-religious person, I would love to believe that our consciousness lives on past our life experience. That said, I’m not sure if it does.

I had a mother who suffered from roughly ten years of serious dementia before passing and there was nothing during her mental decline that indicated that the same conscious being, I’d known and loved as a child was still inside her body.

In the film, the young student Maggie Cupit says that she “hopes” we live on after death, and I fall into that category. Since there’s no way to know, it seems like our best shot is to hope. As for how we define the soul, nothing has changed for me in that regard; I directly equate the soul with our consciousness – that is, our awareness of our self and the energy of who we are and how we define ourselves in this reality.

ATM: How does body, mind, and soul all intertwine or correlate with each other?

CD: As for the relationship between mind, body, and soul, I’d prefer the audience too much greater thinkers than myself – Joseph Campbell comes to mind, indeed Emerson, but also some contemporary scientists such as Richie Davidson at the Univ. of Wisconsin Madison.

We are indeed all aware of our mind-body relationship throughout our conscious lives – and for the most part, these parts of us are inseparable without a strong commitment to meditation and mindfulness. Davidson’s work helps because of his work measuring the brain throughout different meditative and mindfulness practices. There is more, it might seem, to what we are than just our bodies.

ATM: Why is it essential for societal norms to constrain us if one’s life purpose is designed to be different, which goes outside of societal norms?

CD: On the one strong theme that does emerge from the film (and from my overall body of work) is that we are all much more similar than we are different.

In act three of the film, it becomes clear to the students dissecting that once the skin gets removed from the human body, we all look alike. And our bodies function in very similar ways to one another.

So, what makes us unique? Our consciousness? Our thoughts? Our awareness of ourselves? During our short time on earth, I would hope that people find a way to support and love those things that make us the same – family, friendship, the pursuit of happiness – AND the realization that whatever force gave us life also created uniformity inside our bodies.

We all acknowledge our consciousness in our way, and while we may recognize our differences regarding sexual or gender preferences, our economic status, our faith, or our politics, I’ve seen nothing good come from judgment and fear of those who may exercise choices different from our own.

Perhaps, like the students in this film, if we can all acknowledge the similarity of our bodies, then we might also learn to accept the unique choices we’re able to make with our mind and our imagination. Through the dissection process, we learn that our bodies survive because of the extraordinary systems we have inside us that perpetuate life. Is it possible that emphasizing creativity, generosity, and kindness can help us survive and flourish as well?

ATM: Why do you feel these medical students are curious enough to dissect the human body?

Why were you curious enough to film them being curious about dissecting the human body?

DA: (Laughs). It is about 50/50. Some are curious, and some are just going about their business of becoming a doctor. It is a required class. Once they get in there to open the body and pull back the skin, anybody would be curious. They are analyzing what we are. It is who and what we are.