The beauty of the short film medium is how you can tell a powerful story in a condensed period of time. That’s exactly what Lorenzo DeStefano did with his film, “Stairway to the Stars.” The film stars “The Blind Side’s” Quinton Aaron and “Blade Runner’s” Sean Young. The film follows the pair as they make their way up a staircase in Los Angeles. Most interesting, however, is Young’s character, Lavergne, and what the film has to say about the standards of beauty for women. For more information, click here.

DeStefano also published his first novel, “House Boy,” earlier in June. The book was released to rave reviews and he is already working on a screenplay in hopes of turning it into a streaming miniseries.

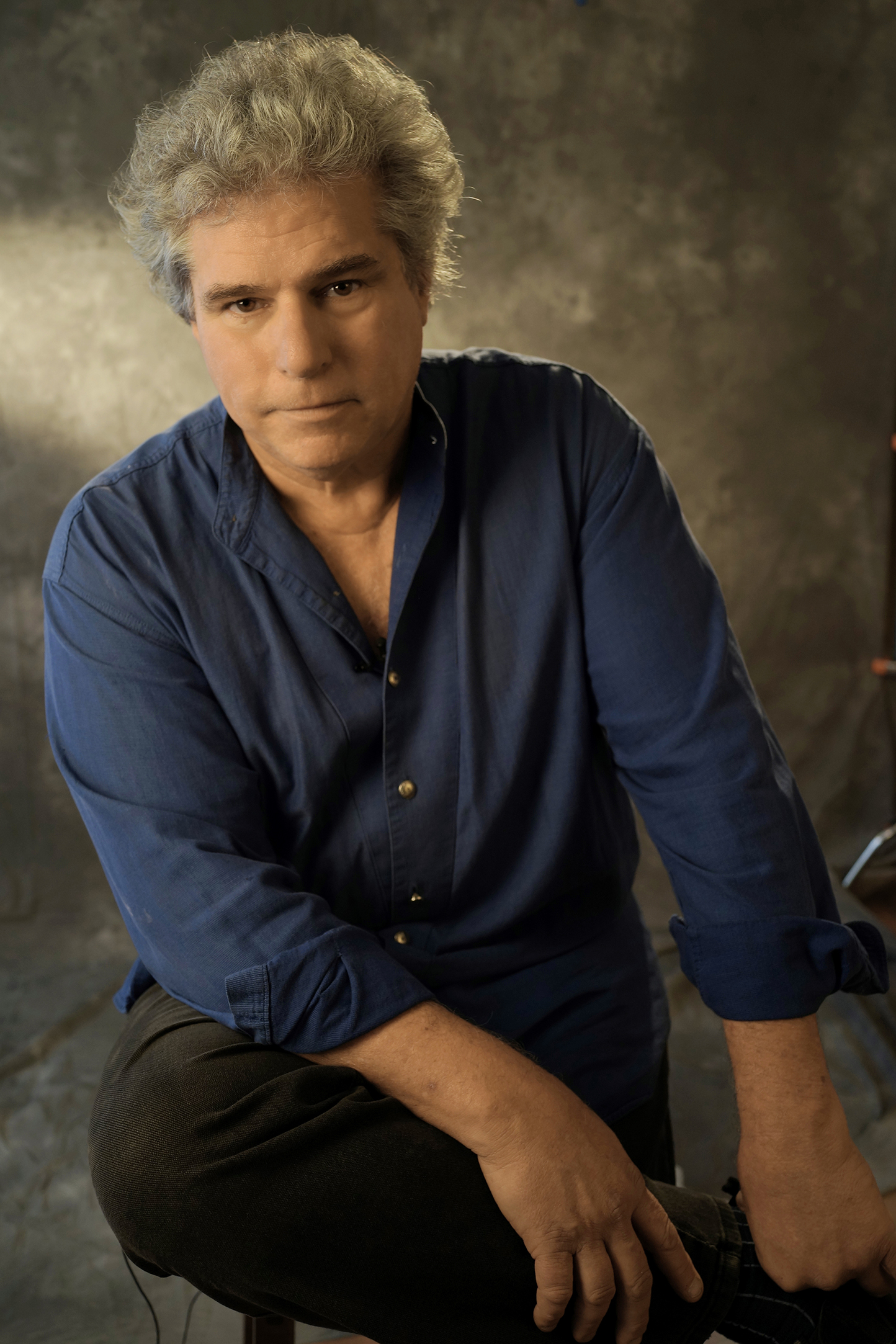

In this interview, DeStefano chats about his experience directing “Stairway to the Stars,” working with the legendary Sean Young, and the process of writing a novel and adapting it on the small screen.

At the Movies Online: I want to start with your short film, “Stairway to the Stars.” I am curious about the idea of the story, was there a particular meaning behind the steps? Or am I reading into it too much?

Lorenzo DeStefano: Well, I think you could go there. In short, when I first moved to Hollywood from Honolulu, I lived up near the Hollywood sign and my place overlooked this staircase — Hollywood is laced with these stairways that connect streets. They go back to the 1920s and they’re all over Hollywood, Silver Lake, [and the] Santa Monica mountains. One day, I’m up there and I hear this shouting, this argument going on and I looked out my window. It was an old lady and a huge fat guy, and they were climbing the stairs and just berating each other, “You old bag, get your skinny ass up there. You’re gonna die,” and she says, “Shut up you fatty. Leave me alone.”

So I listened and when they went out of range, I wrote it down. I was in my late twenties, I said, “I’m gonna make a short film about this,” and I never did. But I did write a little script; I found it a couple of years ago in storage and it was called West Shire Drive — which is where it took place — I rewrote it and I submitted it to a play festival in Honolulu where some of my work had been done by plays and they took it and it was directed by someone else.

I just gave them my blessing and they filmed it and sent it back to me, and the audience was laughing. I said, “I didn’t realize it was a comedy about these two mismatched people,” which gave me [the] confidence to go get two very good actors and I wanted it [the relationship] to be biracial. In Hawaii it was done by an Asian actress and a Hawaiian guy, [but] then I had a connection with Sean Young because of I’ve known her sister for many years. Kathleen Young said, “You should talk to Sean [Young] about this. I think she’d be great for it,” though she was a little young for the part. Anyway, she agreed to do it and then we got Quinton Aaron from “The Blind Side.” We brought him out from New Orleans and she [Sean Young] came in from Atlanta and we shot it. It was a four-day shoot in early October of last year; so that’s how it came together.

ATM: I was going to ask you about Sean Young, you knew her sister then for all these years?

DeStefano: Yes, very well. Her sister [Kathleen] is a writer and a wonderful girl on her own. But I did not know Sean. I knew of her; she’s terrific.

A lot of people ask me, “What’s Sean like? Did she give you trouble?” I mean, she’s a pro, you know? [For] anyone who’s been a star in Hollywood, it’s a perilous road and I thought she was superb in the piece. She was brave. She played a character, not very sympathetic, not physically attractive; we put that wig on her and it aged her 10 years. She was a little uneasy, she was like, “People are only gonna hire me to play old bags now.” I said, “Well, no, you’ll get a lot of positive notes in reviews to the extent a short film gets seen, [though] it’s not quite like a feature.”

She [Sean Young] got a lot of positive notes in a review we just got in Film Threat. It’s our first review as a case in point, the guy really got it, you know, uh, a writer named Alan Ng and he nailed it. He says, “I didn’t even know it was her until they pulled up those photographs on his phone.” Yes. And he goes, “Jesus, that’s Sean Young from ‘Blade Runner,’” and all that.

So I thought that was wonderful to have concealed your real identity so well. And then there’s that little homage to the star that we all know from the eighties.

ATM: Something you touched on there was the idea of beauty standards for women. Like the reviewer [Alan Ng], I didn’t realize she [Sean Young] was in the film yet. You said you wrote the original script years ago, was this theme something that came along more recently?

DeStefano: Obviously, the real people that I witnessed, I don’t [think] she wasn’t an actress, [but] who knows. I developed that relationship, [having it be] an aging actress and a young ambitious guy who wants to be part of Hollywood that was created, the essential dynamic between the real event and the film was this odd friendship; this odd, bitter kind of back and forth, but I had to expand it and I knew I had about 20-25 minutes to do it. And, you know, I hadn’t made a short film since I was a young filmmaker. As you know, short films are often used by new filmmakers to introduce themselves and maybe to get a feature or to expand it into a feature.

This [“Stairway to the Stars”] is done by a veteran filmmaker who just wants to tell a story; I have no interest in expanding it or anything like that. But yeah, the standards of beauty thing came because when Sean [Young] got attached, I said, “Sean, I need to use some photos of you from the past.” And you know, a lot of actresses would go, “No, I don’t wanna see that.”

When in the scene she says, “I’ve been there. I was there when they were taken,” she closes her eyes at one point and doesn’t want to see them. That’s very much how she might feel. As she said to me herself, “You know, when you have that much attention when you’re young, it’s not like anyone else. A normal person’s past is not recorded like that.” So your aging is almost hidden, not that anyone even cares, but women are held to a different standard, and it’s tough.

I thought she was brave to jump in and do this because Laverne is a piece of work, you know? She’s fat shaming; she’s not racist per se, but she’s an old “Karen,” as they say. But anyway, it came out in the rehearsals and she was very active in the rewrite process. At first I thought, “Oh boy, she’s gonna come down on the script now that she’s hired,” “She’s gonna give me some trouble.” She did [give me] some great notes [and] a few things I said, “No, I don’t want to change that,” [to] but other things I said, “Yeah, well let’s let her make it her own.” You have to let go, you can’t be a control freak with these things, but you have to be the watchdog to make sure it’s not going south [or that] it’s going off the rails. Quinton [Aaron] was terrific; I wanted him for the part. [There were] a couple of other people, but I wanted it to be a large guy. And someone [that was] either African American or Asian or Latino to get that dynamic, between them and they [Sean Young and Quinton Aaron] both were total pros. They knew their lines [and] it was a difficult shoot physically, as you could see; there’s no green screen [and] you have to climb those stairs. And three of the four days were on the stairs.

ATM: What did a day on set look like? Because you said you had a four-day shoot, and with minimal actors involved, I’m just curious how big the crew was.

DeStefano: Yeah, it was a tight little crew. Jonathan Hall was the director of photography. It was shot with very nice lenses. [They were a] professional crew who’ve worked together a lot; I had not worked with any of them before. I hadn’t worked with any of these people before; maybe their still photographer and I have done some things.

But the key people had read the script and they come on board. We got lucky with the weather, we got lucky with the permit, we got the location. I rewrote the script once we had that set of stairs, and we scouted a lot of stairs. I thought those are perfect because there are several progressive sections, and I rewrote the script to fit the location.

You know, you’re not gonna shoot it all in one day, so you have to decide, “Day one is from here to here. Day two, you pick up where you left off,” kind of a natural cut point. “Day three from here to the top,” and it was shot in sequence [from the] script for acting purposes and technical purposes; it would’ve been really confusing to jump all over the place, you know? Shooting can go south on you really fast and become a big problem, but this was very smooth. Everybody really got in sync.

ATM: Before I move to your book, what was the transition from editing to directing like?

DeStefano: It’s happened a lot. There’ve been some great editors [that transitioned into directing], David Lean was a fantastic editor from “Lawrence of Arabia,” Robert Wise edited “Citizen Kane” and went on to be a big director, David Fincher, [Martin] Scorsese, they were all editors. They learned in the kind of protected environment of the cutting room, which is very different than the set. It’s not as chaotic. You work on a movie for eight [to] 10 months, maybe more. So you dig in and it’s not for everybody, [there’s] a certain mentality where you can watch a scene an endless amount of times and not be bored by it, you know?

We used to say in the cutting room, “Better is the enemy of good.” In other words, you could be cutting and cutting and trimming frames and eventually you start to harm the thing. [It] seems I learned from a lot of veteran editors who I consulted, who became [I] friends with. I was an assistant — at that time you had to be an assistant for five years before you could legally edit solo — but I worked with two Oscar-winning film editors, Richard Halsey, who won an Oscar for “Rocky,” and Bill Reynolds who won four [or] five Oscars [for] “The Sound of Music,” [he] cut “The Godfather,” “Heaven’s Gate,” and I learned [by] just [being] in the cutting room with those guys and watching them work. I’d occasionally ask them, “Can I cut this little scene” and they’d say, “Yeah. Okay. Go for it.” And then if you did a bad job, they’d tell you what you did wrong. I learned from these guys that just because you’re an editor, [that] doesn’t mean you have to cut like crazy. A great editor reads the film, reads the performance, [and] doesn’t always cut. In TV, you’re banging back and forth. One of the challenges of “Stairway [to the Stars]” was the fact it was dialogue-heavy [and] to find the rhythm in the editing. Monroe Robertson — who’s a young English editor who had cut this for me and with me — I gave him a lot of space to find his own rhythm. And then we worked together for several months. The final cut was version 19, so 19 versions front to back, but [it] takes time. There were some structural changes that I didn’t notice during the script that later on, I said, “Wow, that seems way too late. That scene needs to come earlier.” The apartment scene around the swimming pool, that [originally] happened 20 minutes in, and now it happens 12 minutes in which is information that [the] audience needs. Not everybody’s temperament is right for directing; it’s a whole other deal. You have to be the calmest person. At least in my case, I try to be the calmest person on the set. If things are going badly, you kind of have to use the assistant director to conceal your concern and not share that with the crew because it’s a top-down kind of thing.

But editors are, as a whole — not to generalize — more solitary figures; not too fond of the chaos of shooting and though they would probably make excellent directors, they don’t want to go.

ATM: Can I get your thoughts on the medium of short films and the importance of the way you can tell stories within a condensed runtime?

DeStefano: You can, and the financial risk is less and the time. If it doesn’t work out, you walk away. You can’t do that on a feature, you know? It’s all very perilous, though. Filming is not a natural thing; you’re going against nature to make a film. Documentaries are a little less so, and I’ve done a number of documentaries, but that’s a whole different way of approaching it.

The film I did a few years ago, “Hearing is Believing,” we shot for two years. [It’s a] portrait of a young musician named Rachel Flowers. Wonderful piece, totally different approach. I mean, it’s like short stories. I don’t know if you read books much, but there’s a whole other enjoyment there. There are short story writers who tried the write novels and didn’t succeed. There are some people who do everything well, but that’s a unique form and it’s a great form. And so I think analogous to short films are short stories. You get in there, you tell it and you’re gone. You don’t mess around and it works or it doesn’t work.

ATM: We can transition over to “House Boy.” Are you also trying to adapt this into a film?

DeStefano: Well, it started as a script. Some years ago, I had optioned it to a couple of producers in England and then I pulled it. I realized, “Okay, let me write this as a novel first [and] get it published; it’ll give it a better chance at being made.” Now that the book is out and done and on its way, I went back to writing the script for it as a four-part limited series, which is a format that’s marketable now. Two-hour movies are tricky because the theaters are taken over by big tentpole movies, as you know, so streaming services are the place to go to tell more serious stories without having to compress everything into two hours. So I’m writing a four-part limited series, four one-hour scripts, roughly. And I’m enjoying it. I’ve done a lot of screenwriting, so I’m familiar with the transition. I’m throwing out a lot of stuff from the book, [stuff that’s] just not translatable. So hopefully I’m the right guy to do that job, we’ll see. I’m about halfway through the first hour and I’m just continuing to explore.

ATM: And this was your first novel, correct? What was that process like? I know you’ve done a lot of screenwriting, but I imagine there’s a difference in those writing styles.

DeStefano: I, like a lot of writers, tried to write a few novels in the past that [I] didn’t quite complete and dropped them. This one [“House Boy”] was a true story. The documentary background is helpful because I do key off of true events. I have a lot of respect for people that invent things completely from nothing, I guess I need a little bit of a kickstart, a little something to get me going. It was an article I read, I was in England for a reading of a play of mine, and I read a little article in the newspaper about a young man who was convicted of murdering his employer and was in prison. I’ve been interested in modern slavery as a phenomenon and I contacted the lawyer for this young man. And I said, “I’d like to interview him in prison, maybe write an article or journalistic piece about his experience.” And it was arranged, he agreed. He didn’t speak much English, but it was arranged. And so the day before I was supposed to go to Brixton Prison, which is a big prison in south London, he was deported back to India, so I never got to meet him. And I tried to find him, [but] it was impossible. He just fell back into the cracks of his world.

So I put it away for a while, but it kept gnawing at me, it was one of those stories. What was interesting is that it was a young man who was sexually enslaved by a woman; it’s usually the other way around. You don’t see too many of those stories. So I said, “Okay, this is different,” and over a long period of time, the last couple of years I buckled down and I kept writing and writing and writing. I wanted to finish it and see if it would actually come off, you know? I found a publisher, Atmosphere Press out of Austin, Texas, and they took it and it spent about a year-and-a-half in editorial, working with different editors, including the young woman from India who helped [as] a cultural advisor, and it came out to June 7th. So yeah, long road. It’s been very gratifying. It’s been getting good reviews and people are getting it. When people get your work, that’s the best thing, whether it’s in a movie theater and you’re sitting in the back and they’re laughing or they’re into it, or reading it. Publishing novels is not my world, but I’ve learned a lot. I’ve taken a lot of advice from people and the publishers included and I’m just riding it, riding the little wave that’s been created. But I’m pleased and it seems to be taken as an important story. It’s an urban thriller, but it has a sociological backdrop in reality, which is [that] these kinds of cases are happening all the time.

ATM: I didn’t realize this is based on a true story, so what did you hope readers of the book and future viewers of the limited series take away from this story?

DeStefano: The adventure of reading or watching films, [or] in this case, reading, you’re opening yourself up to worlds that aren’t your own, and that’s a healthy thing. The problem is we’re seeing it in our culture, how people hang onto their belief systems, whether it’s on the left or the right they’re very protective of their beliefs and reading is a great way to destroy your expectations, shatter your preconceptions. And if you’re in the hands of a skilled writer, I think whether it a film or fiction or non-fiction, you need to feel a certain amount of trust in the storyteller whether it’s [Herman] Melville or Edgar Allen Poe or any of the great writers, you trust them, you say, “I’m on this ride with you; take me where you take me, where you want [this] thing to go,” and that’s a privilege that people spend their hard-earned leisure time reading your stuff. So I don’t know, I hope they get revelations about lives outside their own, some sensitivity about issues like this, but I’m not trying to teach anybody anything. It’s more just a hell of a good story that you can’t put down and that seems to be the general reaction is that people are gripped by it, and that’s a good thing.

ATM: I know you’re very early in the writing process of the miniseries adaptation of “House Boy,” but are you hoping to direct the series? Or are you hoping to hand it off to somebody else?

DeStefano: I never wanted to direct it. I think you gotta pick and choose. One of the main reasons is that I think it should be directed by a south Asian director. An Indian director, or an Indo-British director, man, woman, anything in between, [it] doesn’t matter but their cultural take on it needs to come into the picture. I guess I’m a little sensitive about being from outside the culture. I’m glad that the book has been received without me even being taken into account. I made a film in Cuba some years ago about a group called “Los Zafiros: Music from the Edge of Time,” and the biggest compliment I got from Cuban people was that they thought it was made by a Cuban filmmaker, which was great.

I’m not into the cult of personality, I’m interested in it when I see it like with [Donald] Trump or anything like that, that’s a cult of personality at work. I think it’s dangerous, you know? But I’d rather not be the topic of conversation. It should be the story that I wrote, but I’d like to have someone else direct it who’s closer to the culture who could bring a whole other value to it.

ATM: Maybe you would be able to answer this, maybe not, but when you’re writing the screenplay, are there any actors that you kind of picture in the series?

DeStefano: There are people out there that you see in movies like Riz Ahmed, [who] is a South Asian. I wrote the part of the detective with Irrfan Khan in mind. I think he was in one of the “Jurassic” movies (note: Khan was in “Jurassic World”), [but] he kind of went back and forth between Bollywood and Hollywood movies. He died very young a couple of years ago at 54 years old, [which] was devastating. But Khan was my model for the detective.

But that’s another reason for an Asian, or South Asian director to come on because they know who’s out there in that world. You know, the cast is largely South Asian, there are some English actors as well, you’ll see when you read it, it’s quite a big cast and it’s not a cheap movie. It’s you got to shoot in India for a few weeks, you [have] got to shoot in England, it’s sprawling in that sense, even though it largely takes place in the house. There are a lot of other things that are happening outside of that world, in his imagination.

So yeah, I’ve used actors as a model, but then it’s just a launching point. The likelihood of getting them is tricky, that’s a whole other story. But in this project and another project of mine called “The Diarist,” I was attached to direct that with John Hurt, you know from “The Elephant Man” and “Midnight Express,” great actor. He died a few years ago, John and I were partners to do that [but] we couldn’t get any funding for us. After John died, I decided to rewrite that as a five-part limited series because I’d spent years trying to compress it as a big story. It’s about a man in Boston who wrote a 17 million-word diary, a man named Arthur Inman. And I’ve had the rights to that for some time. It was done on stage, I wrote it as a play, and I decided at that time to step back as a director on that one as well because when I rewrote it as a series, it became a $35-$40 million movie and I know I’m not gonna get approved for that by Netflix or Amazon or HBO or whoever. So facing reality is a tricky thing. You’ve gotta say, “They’re never gonna let me do that, but they would let someone else do it. Someone who’s on their list are who they just finished the series with.”

[With] “House Boy,” I became attached as a producer-writer and [will] hopefully hang onto the writing as a solo credit, but [it’s] quite likely to have other producers on board as well. But I own the underlying rights to the book in that case and “House Boy,” same thing, so there’s a little bit of protection there. But you have to give up, it’s not like everybody’s Orson Welles out there [that can] do it all. Orson Welles’ career, as you know, was not an easy one. I’m sure if he would’ve done some things differently, as brilliant as he was, he tried to do too much and it hurt him in some ways, you know?

For more information about “Stairway to the Stars,” click here. For information about “House Boy,” click here.